BOTLEY WEST SOLAR FARM INFORMATION

Botley West is a 840 MW solar park proposed to be built to the West and North of Oxford. The second phase of consultation ended on 8 February 2024.

Low Carbon Hub and its local community shareholder groups worked together on responses to the Botley West Solar Farm proposal because the groups work in the affected communities and Low Carbon Hub exists to support its shareholder community energy groups.

Following the announcement of the Botley West project, Low Carbon Hub was approached by a number of stakeholders, including our investors and local community groups looking for support to better understand the implications of the project.

As a result, we attended the formal consultation meetings and listened to people’s questions, invited people to submit their questions to us either at the consultations or via our website. Our aim has been to help local communities access further information relating to the potential impacts and benefits of the scheme to inform their own response to the formal consultation. We have been acting entirely independently from the project.

Through this process we received over 70 queries and responses relating to the proposal, and broader queries relating to ground mount solar in general, which we have posted below along with answers we’ve researched.

Community benefit proposals

Low Carbon Hub and local community shareholders – GreenTEA, Sustainable Woodstock and Sustainable Botley – submitted this response to the formal consultation on community benefit.

Since we submitted this proposal (in February 2024) and consulting with experts in the field, we have developed our thinking in relation to what constitutes a ‘fair’ community benefit package. This led us to launch a campaign asking for 2% of project revenue to be invested in communities.

Make Botley West Fair Campaign

In April 2025 we launched a petition aimed at Blenheim. Calling for them to use their influence to secure a better community benefit deal from the developers – one that reflects the project’s scale and supports local communities. You can find out more about our campaign and sign the petition here.

Q&A

The project and the electricity network

Why here? Why now?

Many community members are keen to understand the ‘why here?’ and ‘why now?’ questions around Botley West.

The answer to this question is difficult to pin down completely clearly because of the way the UK’s liberalised energy system is governed. What we understand the position to be is:

- The Didcot A coal-fired power station had the capacity to generate a maximum of 2,000 megawatts (MW) of electricity and used 300 kilotonnes of coal per year. Its closure in 2013 left capacity on the transmission network for the same amount of generation, specifically the 400 kilovolt (kV) line that runs north and west from Didcot. The transmission system is like the spine of the whole thing, moving electricity very quickly between different areas of the country – it is generally what we see as the lines of pylons that march across the landscape.

- We are trying to understand whether and how the closure of Didcot A has contributed to the increasing difficulties being reported in getting electricity into Oxfordshire. We are also trying to understand what the nature is of the ‘upstream constraint’ on the transmission system that is preventing a sizeable pipeline of local renewable energy projects from being built. And whether that constraint will be solved by the new 400kV substation being built as part of the project.

What we have learnt so far, is that we need to separate our understanding of the flow of electrons from the flow of money: so the flow of the electrons is very complicated and, so far as we understand it from those in the industry, a bit meaningless, as least so far as the customer is concerned. So we shouldn’t worry too much about whether we are using ‘our’ electrons as they are produced, the kWp; the system is there to manage all of that and to balance the sources of renewable energy against the amount of electricity we use at any particular point in time.

What is more important is the total amount of renewable electricity produced and that we know we are balancing so far as we can our production with our demand in kWh. So it is important for us all to contract to buy renewable electricity and that we are concerned about how much of that electricity is produced locally, i.e. how that balance of production and demand matches over time. There seems to be a growing view that being able to buy the electricity directly from local sources would be beneficial.

Finally, the nature of the upstream constraint seems to be about the total amount of generation trying to connect to the National Grid and about the connections system that governs that. It is good news that there is 60GW of renewable electricity in the queue to connect; less good news is that the queue management system was designed some decades ago and is not up to the job. So Botley West will not have a direct impact technically on relieving the constraint on local (distribution scale) renewables.

A note of caution: this is my interpretation of recent discussions with very expert people. I have done my best! - So, as we understand it, the National Grid wants to use the capacity to move generation that exists on the transmission system, but needs to build a new 400kV substation to be able to access that transmission. The Grid Code that governs what the different bits of the electricity system can do, prevents the National Grid from just proposing and building a new substation; it has to be responding to developer need. Another way of putting it is that it is not allowed to ‘invest ahead of need’ but has to find a developer who needs the capacity.

- The proposed 400kV substation will have 3GW of capacity for connection of new generation. So Botley West will only take part of it and there will be room for around two other proposals to come forward along the 400kV line. Our understanding is that it would be unlikely these would be in Oxfordshire. We are trying to find out whether the proposed substation can come forward based on just the one developer’s need, or whether others are needed to make the case.

- The only type of renewable generation Oxfordshire has enough technical capacity for in a single place is solar PV. Our wind resource is not great because we are an inland county, we already have two large Anaerobic digestion (AD) plants taking our food waste, we have the waste incineration plant already at Ardley and our hydro resource is small and tied, obviously, to the course of the Thames.

- So the Grid had a need, a developer was looking for opportunities and the final ingredient needed was land. It is obviously preferable to be working with as few landowners as possible for this sort of project and Blenheim has a lot of land in a single ownership. Others could be added, but Blenheim is the anchor. So the proposal is 840MW in size because that fits the land available.

Many will find it surprising that our electricity system has so little ability to develop strategic projects independently as we are trying to transition to renewable electricity so that we can achieve our net zero targets. Probably no-one involved in this project would disagree with that view. - In answer to questions about the wisdom of connecting all the bits of Botley West together, this is proposed because the project needs to act as one site in order to justify the transmission level 400kV substation and so get the connection. With the current constraints operating at the local primary substations on the distribution network, it would be very expensive and lengthy process to make the separate applications and unlikely to produce success for many, certainly not all the applications.

How big is the Botley West proposal?

Video answer by Professor Nick Eyre at ‘Clean Energy: Why Here, Why Now?’ event on 26 October 2023

Overview: Botley West is certainly big by standards of current solar farms. It’s about a fifth of the solar energy that we think Oxfordshire will need by 2050. The proposed Botley West area is approximately eight square kilometres, equivalent to about a fifth of Oxford City or 0.3% of Oxfordshire’s total land area. So the perception of its size depends on the perspective applied.

Why is a proposal of this size being proposed here?

Video answer by Professor Nick Eyre at ‘Clean Energy: Why Here, Why Now?’ event on 26 October 2023

Overview: The proposal is tied to electricity network planning. There is a major transmission line that runs north to south through Oxfordshire. Didcot A, a large coal fired power station which was connected to this line was was closed in 2013. As a result there is space, in electricity capacity terms, for a big electricity generating station in the middle of Oxfordshire.

I was told today (Cumnor) that the main substation by Farmoor Reservoir (black & white stripes on map) is “coming anyway” and that the Botley West substation is a small add-on (orange box on map). Is this correct?

Question from: Stuart, Farmoor

No, that is not correct, as we understand it. The hatched area is for the 400kV substation that would be owned by the National Grid. The orange bit on the side is the solar farm substation. The 400kV substation needs the development if it is to happen because the National Grid is not allowed to ‘invest ahead of need’.

The team today said that the Red House Solar Farm is “number two in the queue” (e.g. to build a substation). Is this correct, or is it likely that both projects will proceed at the same time?

Question from: Stuart, Farmoor

Our understanding is that this is not correct. The Red House Farm application is for a much smaller installation – just under 50MW rather than 840MW. This means that it will be connected to the distribution network not the transmission network.

I notice that it is anticipated BWSF will generate enough electrical energy to supply 300,000 homes. Between now and 2050 electricity use in homes is expected to double or even triple as electrification of heating and transportation takes place. Is the 300,000 homes prediction based on today’s average electricity use, or the predicted future consumption per household?

Question from: Amanda, Standlake

It is based on today’s consumption averages and so the contribution of Botley West will go down over time.

Can we not just do more rooftop solar?

We need both rooftop and groundmount to be able to reach our net zero targets.

As Prof. Nick Eyre states in this video (1:40:59) (from Sustainable Woodstock’s ‘Clean Energy Why Here & Why Now’ event, 50% of our solar potential will come from rooftop solar (domestic, business and schools) and 50% from ground mount solar, so we need a “substantial contribution from both”. Therefore, rooftop solar alone won’t meet our needs.

Is an entirely new substation needed, or can existing ones such as the one in Yarnton be expanded?

Question from: Anon.

This piece of SSEN evidence for the RIIO-2 investment round may be helpful here. It identifies Yarnton as a Bulk Supply Point (BSP) rather than the Grid Supply Point (GSP) substation that is proposed for Botley West. GSPs are owned by the Transmission System and step the voltage down from 400kV to 132kV. BSPs are owned by the Distribution Network Operator and step the voltage down from 132kV to 66 or 33kV. So our understanding is that Yarnton cannot be expanded to become a GSP when its job is to be a BSP.

Have alternative locations for the substation been examined?

Question from Anon.

Our understanding is that a new Grid Supply Point (GSP) is required on the 400kV line that runs north/south via Didcot. The process currently in place for proposing investment in new grid infrastructure is that a developer need must be demonstrated; the Energy System Operator (National Grid) cannot propose investment ‘ahead of need’ according to the Grid Code put in place in the late 90s to govern a ‘liberalised’ energy system. The Botley West proposal demonstrates that need in this location. We do not comment on the fitness for purpose of that piece of the Grid Code as we transition to a decarbonised energy system.

Could the need for a new substation be avoided – and would it not be cheaper and quicker for the nation – to locate the solar panels near the existing electricity system infrastructure in Didcot?

Question from: Anon.

Our understanding is that the new substation is required by the transmission system anyway. Location of a solar farm near to Didcot would therefore not make that need go away. See the answer to the above question for the way that new investments in the energy system infrastructure are governed by the Grid Code.

Biodiversity and land management

What does “70% biodiversity net gain” mean? How will biodiversity be monitored?

Questions from: Anon. Woodstock & Sarah, Eynsham

New legislation comes into force shortly whereby all developers (except those of very small developments and rail projects) must provide 10% biodiversity net gain (BNG) over and above the original condition of the land. So they must mitigate any loss they cause during construction and then provide 10% on top. The guidance on BNG is here.

The biodiversity gain is measured in units and these are set according to the habitat being affected. Any soil improvement is not counted; it has to be above ground. There is a separate set of guidance on metrics here.

If a developer cannot provide the required biodiversity net gain on their site, they can buy units from the market. Early indications are that each unit of biodiversity will cost around £25k. Conversely, if developers can provide more than the required 10%, then they can trade the surplus and make money, but this has to be explicitly included in the planning permission.

The biodiversity net gain is monitored over the 30 years it has to be in place by ecologists who are paid for by the providers of the BNG from the income created from the credits. It is all governed by a legal agreement that is registered with all the relevant authorities.

For Botley West, the situation seems to be:

- There will be substantial soil improvements gained by the land not being farmed using modern practices but this is not included in the BNG figure;

- The developer will be required to provide 10% BNG but is offering 70%;

- Much of the BNG could be provided by things required by the planning process, e.g. new hedgerows for buffering views;

- The 60% offered over and above the legal requirement could be traded on the new BNG market and so increase the income from the site.

How will the site help biodiversity given that it will be covered in solar panels?

Video answer by Dr Jonathon Scurlock at ‘Clean Energy: Why Here, Why Now?’ event on 26 October 2023

Overview: With planning development now mandating measurable biodiversity net gain, incorporating this into solar farm development is considered good practice. Wildlife, from insects to small mammals, can find refuge in solar farms due to minimal disturbance. Contrary to misconceptions, solar farms can be effectively managed for biodiversity without impeding plant growth or ecosystem function.

What impact might solar panels have on food security?

Video answer by Dr Jonathon Scurlock at ‘Clean Energy: Why Here, Why Now?’ event on 26 October 2023

Overview: The speaker encourages high standards in solar industry practices, having collaborated with Solar Energy UK for the past decade. While advocating for sparing better-quality land for more flexible agricultural production, they acknowledge the national scale impact of solar farms as a small percentage (less than 0.1%) of utilised agricultural area.

The figures calculated by Professor Nick Eyre at the University of Oxford show that even if 100% of the total energy demand in 2050 was provided by ground mount solar then that would only need 2.5% of the UK land area to accommodate it.

In reality, ground mount solar will only need to provide 20% of our energy needs and this equates to taking up just 0.5% of the UK land area. This is about the same as currently taken up by golf courses across the UK.

Nick Eyre, Professor of Energy and Climate Policy at Oxford University says:

“Opponents of renewable energy often cite the very large land area required. But for solar energy, it is a myth. The UK could supply 20% of the total energy we will need in 2050 using solar panels, by covering only the same area currently used for golf.”

What provision will be made for ongoing maintenance of the site including monitoring biodiversity and adopting measures to increase wildlife friendly opportunities, such as prioritising suitable habitats?

Question from: Jenifer, Woodstock

Our understanding is that the Blenheim Estate will manage this. Further, the Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) elements are provided under a legal contract with a local authority, in this case West Oxfordshire District Council, which includes funding for ecologists to monitor that the BNG is being provided as stated over 30 years.

Will there be livestock kept alongside?

Question from: Jane, Oxford

The developer is considering options for this with the landowner.

Given existing use of land (e.g. farming) and extensive use of pesticides, herbicides etc. biodiversity would seem to be poor generally. 70% of improvement seems insufficient. How do the developers propose to exceed 70%?

Question from: Darrell, Woodstock

Biodiversity Net Gain is a new method of developments being required to provide improvements. The legal requirement is 10% over existing, i.e. before any harms caused by development. So the land has to be restored to the status quo and then 10% provided on top of that. So the 70% proposed here is a long way over the legal requirement.

Has the planning for the farm and its connection to the grid taken account of important sites for wildlife – noting that high quality flood-plain meadows can not be offset or recreated in any meaningful way or timeframe?

Question from: Robin, unknown location & Eleanor, Eynsham

The developers information shows flood plain maps with all the level 1 area left free of panels. Current farming is on level 2 areas. So the conclusion would be that remaining flood meadows are retained. It should be noted that the current plans are still provisional with final ones only being available with the final application of the Development Consent Order and the submission of the final Environmental Statement to go with it. The Environment Agency is a statutory consultee on the application.

Could the sites biodiversity be managed by a community organisation funded by the development? Otherwise how can we be confident in future management?

Question from: Anon.

We are happy to put this idea to the developer as part of a consultation response on community benefit.

Biodiversity net gain – 70% in the plan – how is stewardship assured in the future?

Question from: Lucy, Eynsham

This is governed by a legal agreement signed between the developer and a designated third party – our understanding is that this would be West Oxfordshire District Council. Cost of ecologists to monitor delivery is part of the agreement.

Please can I know how much agricultural production will be lost (in terms of grain per year) as a result of this proposal?

Question from: Chris, unknown location

Our understanding is that the land has been used mainly for grains and pulses with a small amount of grazing. Production has gone mainly for animal feed and for energy (Ardley and bio oil). Yields are generally below national averages, ranging from slightly below to almost 50% below, with the average being about 10% below. Our understanding is also that not farming the land with modern practices would save around 800 tonnes of fertiliser being applied.

Community benefit

What level of community benefit is suitable for such a project?

Question from: Darrell Marchand, Woodstock.

Community benefits are a voluntary package of benefits (usually financial in nature) that renewable energy businesses provide to support communities in which they operate.

There is no set amount that businesses should offer for community benefit. Here are a couple of examples of different amounts being suggested at other renewable energy projects in the UK:

- Local Energy Scotland suggest £5k/MW/year installed and index-linked for the life of the project. This is for windfarms and they, of course, produce more energy per MW installed than solar does, so not a direct comparison. This would amount to approximately £4.2m/year.

- There is an 800MW proposal for a solar farm in Nottingham. The offer being discussed here is £1,200/MW/year. This would mean around £1m/year.

Botley West developers have initially suggested they would offer £50,000/year in community benefit.

If you have suggestions of what good community benefit could be, please let us know via email to info@lowcarbonhub.org.

Here are some ideas, suggestions and comments we’ve received on what community benefit the project could support:

“I would love a Nature Reserve to be established in the Magic Island Field, south of Bladon, north of Cassington. Also a footpath along the Evenlode. It would be wonderful to establish a beneficial biodiversity for the magic field. And work with local schools via citizen science” – Jeanie, Bladon

“An interpretation centre at Purwell Farm that could overlook a beautifully designed solar farm if designed as a whole to be beautiful” – Anon. Woodstock

“The size of Community Benefit Fund needs to be large enough to fund small capital projects such as PV on community buildings, churches etc.” – Larry, Enysham

“Could Botley West fund the B4044 community path (cycle/pedestrian)? This has been campaigned for approximately 20 years, has huge support would be well used and is ready to go!” – Anon. Eynsham

“Will there be support for the Botley / Eynsham cycle path?” – Karen, Botley

“Community benefit can offer seem very small relative to the size of the project. Something like £400k+ would be more like it.” – Anon. Woodstock

“Current proposals to match £50,000 from Blenheim for all the project does not seem enough. I would suggest £1million plus would help people feel more positive about the proposals.” – Karen, Botley

“Some of the profits should go to the communities affected. Why not solar on Salt Cross Garden and rooftops?” – Anon. Eynsham

Renewable Technology

Why can’t we have bi-facial panels vertically with farming between?

Question from: Michael, Bladon

Bi-facial solar panels capture light from both the front and the back as a back sheet allows the sunlight to reflect off the ground and be captured by the panel. This means they capture more sunlight and generate more clean electricity per area of solar panel.

At the Low Carbon Hub we’ve used bi-facial panels in our ground mount solar park, Ray Valley Solar. We are in the first year of this project and are monitoring their effectiveness. So far, we have found an uplift in generation from those modelled for uni-facial panels, especially in winter months.

Some experimental designs also allow for the angle of the panels to be temporarily changed, to allow for farming equipment to pass between the rows of panels.

Can you provide endorsed technical data on the relative total carbon lifecycle footprint of the three main renewable energy technologies – wave, wind and solar?

What is the embedded carbon and how long will it take to pay back?

Questions from John Orme, Woodstock and Anon. Woodstock

The environmental benefits resulting from the electricity generation by solar panels, needs to be considered alongside the environmental cost of producing and installing the panels. The payback time relates to how long it takes for the carbon saved from the generation of green electricity to recoup the cost, in carbon terms, of the installation. The precise payback of any installation will vary depending on factors such as: the efficiency of the panels, the source of the energy used to manufacture them, manufacturing methods and the distance and mode of transport used to get them from manufacturing to site.

The total carbon impact of renewable energy projects is shown to provide a net benefit over their operational lifetime. For solar PV the speed at which that benefit is achieved is increasing due to the increase in performance of the panels and manufacturing techniques (Louwen et al 2016).

For onshore wind this can vary, it is found that larger scale sites / turbines provide a faster means to net benefit (Smoucha et al 2016). We have little to no experience of “wave” energy and the multiple technology types that utilise it. However, individual studies indicate similar net benefit and are of course dependant on the sourcing of steel and the process of maintenance.

Because of these varying factors the payback period for Botley West will depend on the choices they make about sourcing their panels and installation. It would be reasonable to assume that, as stated in the video clip below from Sustainable Woodstock’s ‘Clean Energy Why Here & Why Now‘ event, it will fall somewhere in the 2 to 6 year range, with the scheme becoming carbon positive fairly early in its overall life.

Below are a number of articles and studies showing the variation in life cycle assessment for renewable technologies at different scales.

- ‘Solar panels repay their energy ‘debt’: study’

- Energy payback time and carbon footprint of commercial photovoltaic systems

- Re-assessment of net energy production and greenhouse gas emissions avoidance after 40 years of photovoltaics development

- ‘Life cycle costs and carbon emissions of wind power‘

- ‘Full Life Cycle Assessment of a Wave Energy Converter‘

- ‘Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions and energy footprints of utility-scale solar energy systems‘

- Life cycle analysis of the embodied carbon emissions from 14 wind turbines with rated powers between 50Kw and 3.4Mw‘

Is there a cost estimate for decommissioning after 35 years? Presumably there should be a bond for this amount in the contract?

Question from: Anon. Woodstock

The Botley West Phase two consultation booklet states: “At the end of Botley West’s operational life, a comprehensive decommissioning plan, commencing two years before the lease concludes, will be executed. Our commitment is to remove all infrastructure except public highway cables, keeping the National Grid substation. The land will return to its original use, and not become brownfield land, with a dedicated reserve to cover decommissioning costs.”

It would be normal practice for this to be covered as a condition by any planning approval and for the costs to be dealt with in any contract between the developer and the landowner.

We have approached the developers for further information regarding a cost estimate for decommissioning costs.

I would like to know what the carbon footprint of importing 2,600,000 solar panels is. And the carbon footprint of the de-installation

Question from: Lynda, Eynsham

Understanding both the carbon payback, and wider whole life cycle assessment of the project, which takes into account the energy and impact of the project from start to finish would be helpful in understanding, and assessing net benefit in environmental terms of the project.

We understand that the whole life carbon calculation will be done at the next stage of the project development by the Botley West developers.

Going forward, there may be other factors other than purely carbon payback which can be helpful measures of the impact of solar projects. This article gives further details.

How are the panels recycled? Is the process of producing the equipment detrimental to the environment? Is the mining of the materials bad for the landscape in those countries? What about slave labour in those countries?

Question from: Philip, location unknown

The majority of the materials that make up solar panels, including aluminium, silicon, glass and plastics are indeed recyclable. However, recycling solar panels is difficult to do. Ensuring that the infrastructure exists to ensure this happens is important for the whole transition to net zero.

The good news is that solar panels are lasting much longer than they used to: in the region of 30—35 years (where it used to be more like 20 years).

With regard to mining materials needed for renewables, in the video clip below from Sustainable Woodstock’s ‘Clean Energy Why Here & Why Now‘ event, Jonathan Porritt says “we need to be far more applied to ensuring that the flows of materials which will be needed come with lower impact in terms of mining that is currently the case.”

He states that we should insist on the decommissioning and recycling of panels and goes on to say “These are big and legitimate issues to be talking about, they are not deal breakers when it comes to solar power, being such an important part of the total energy mix of the future.”

Could there be a time limit set for the solar panels after which time they would have to be removed? Would it be more acceptable to have wind turbines?

Question from: Rod, Freeland

The developers have stated:

“At the end of Botley West’s operation a robust decommissioning plan will be put into action. This plan will be included within our Development Consent Order (DCO) application, when acquiring consent to build Botley West. The plan will set out how the infrastructure will be removed and the land reinstated. At the end of the period of consent, the land returns to agricultural use. A dedicated decommissioning reserve will be created which will cover the costs of removal and reinstatement. The overall lifetime of Botley West Solar Farm is currently anticipated to be circa 42 years.”

With regard to wind turbines, there have been extensive surveys looking at the contribution wind power could make to Oxfordshire’s energy mix. As Prof Nick Eyre sets out in the video clip below from Sustainable Woodstock’s ‘Clean Energy Why Here & Why Now‘ event, wind will make a low contribution to our electricity within Oxfordshire as an inland county, but a big contribution to the UK’s energy mix.

I cannot find the estimated annual energy output for the project. I would be interested to see the estimated energy output against time.

Question from: Anon. Woodstock

Yield for solar generation is usually based on PV Sol and PV Syst models industry standard models for designing and optimising solar PV schemes in the UK and globally. These models calculate the amount of solar radiation hitting the panels. The amount of irradiation captured is then determined by the pitch and orientation of the panels. In ground mount solar it is possible to position the panels to capture as much of this irradiation as possible. These models are solar of all scales from rooftop to this sort of groundmount development and, in our experience, are very accurate.

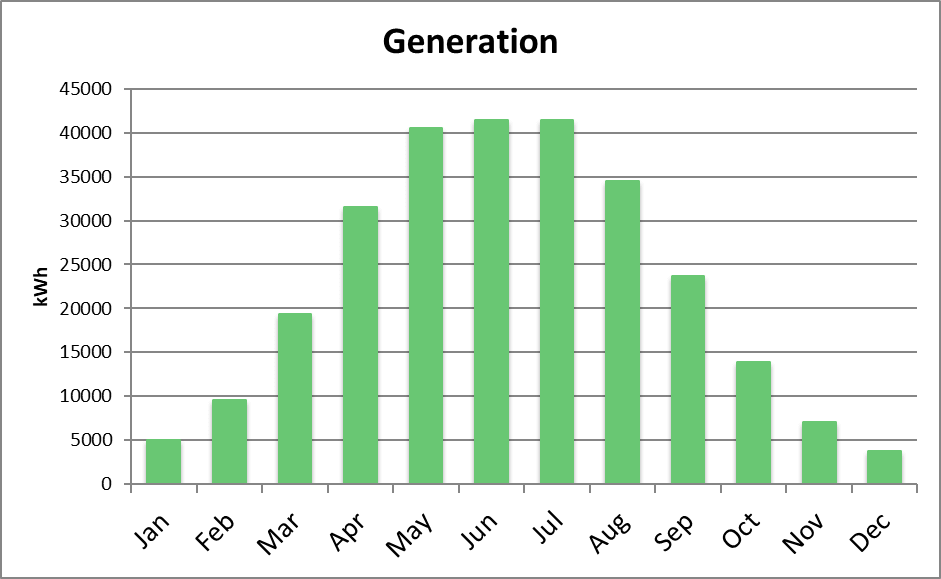

We have asked Botley West to confirm their modelled power output. By way of comparison, Low Carbon Hub’s 19 MW Solar Farm at Ray Valley Solar in Arncott is estimated to generate 19.5 GWh each year – although we haven’t had a full year of generation yet, so we don’t have the complete data. Here is an example of how solar generation would look over the course of a year, based on our ground mount solar park.

Other solar farm projects locally include Southill with an estimate annual energy output of 4.4GWh and Westmill Solar with 4.8GWh each year.

The site

Will the security from the site e.g. lights and cameras be intrusive to local neighbourhood?

Question from: Anon. Bladon

Our understanding from the developer is that the site will be monitored using an infrared system that means no security lighting is needed or regular security patrols.

The visualisations presented so far showing what the development would like after 1 year from various viewpoints do not appeal. Is that because proposed screening etc. has not developed or is the screening inadequate? What will it look like in 5 years?

Question from: Darrell, Woodstock

Our understanding is that at this stage of proposals the developer can only show viewpoints for year one. The full application stage will include details of how it will look in five years. However, we are checking this with the developer.

My concern about the ‘Botley West Solar Farm’ is that they are bypassing the local planning process – is this a construct or is it reasonable?

Question from: James, Cumnor

The Botley West solar farm goes through the National Strategic Infrastructure Planning process by virtue of its size. So, given that the developer has chosen to develop a 840MW scheme, this means that it is not dealt with locally. Please see answers ‘Why here? Why now?’ above for our understanding about why the proposal is for 840MW.

How would the agreement work between the developer and the community? Commercially, Physically, and Financially?

Question from: Anon.

There is no set process for negotiating, agreeing or monitoring community benefit agreements in England. Scotland has a very robust policy and system and Wales is rapidly catching up. We would expect one of the local authorities to be the signatory. We agree that it is not clear to the community and that this does not help to build trust. Low Carbon Hub will do its best to advocate both for proper amounts of funding, but also, and in some ways more importantly, for funding agreements to include proper governance, with the community involved, and clear outcomes that can be monitored. It is very important indeed that any annual funding agreement includes index linking to make sure it keeps in line with inflation.

What about community ownership via co-ops fed by electricity public holdings. Remark: within a distance of solar farm gets share of the energy produced

Question from: Anon.

We agree that community ownership options should be explored, as well as the exciting ‘smart’ business models suggested by the potential SolarRetail supply company the developer is investigating.

Comments

Comments received

I am very much in favour of solar energy in addressing climate change and approve of the scheme. I think it is making great efforts to consult with the community